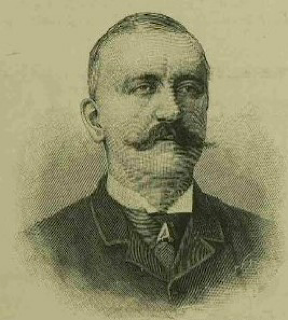

Charles Frederick Williams, a Scottish-Irish writer, journalist, and war correspondent, dies in Brixton, London, England, on February 9, 1904.

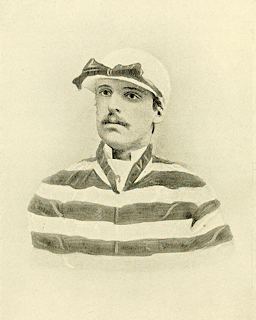

Williams is born on May 4, 1838, in Coleraine, County Londonderry. He claims to be descended on his father’s side from Worcestershire yeomen living in the parishes of Tenbury and Mamble. On his mother’s side he descends from Scottish settlers who planted Ulster in 1610. He is educated at Belfast Academy in Belfast under Dr. Reuben John Bryce and at a Greenwich private school under Dr. Goodwin. Later on, he goes to the southern United States for his health and takes part in a filibustering expedition to Nicaragua, where he sees some hard fighting and reportedly wins the reputation of a blockade runner. He is separated from his party and is lost in the forest for six days. Fevered, he discovers a small boat and manages to return to the nearest British settlement. He serves in the London Irish Rifles and has the rank of sergeant.

Williams returns to England in 1859, where he becomes a volunteer, and a leader writer for the London Evening Herald. In October 1859, he begins a connection with The Standard which lasts until 1884. From 1860 until 1863, he works as a first editor for the London Evening Standard and from 1882 until 1884, as editor of The Evening News.

Williams is best known for being a war correspondent. He is described as an admirable war correspondent, a daring rider as well as writer. For The Standard, he is at the headquarters of the Armée de la Loire, a French army, during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. He is also one of the first correspondents in Strasbourg, where the French forces are defeated. In the summer and autumn of 1877, he is a correspondent to Ahmed Muhtar Pasha who commands the Turkish forces in Armenia during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877 and 1878. He remains constantly at the Turkish front, and his letters are the only continuous series that reaches England. In 1878, he publishes this series in a revised and extended form as The Armenian Campaign: A Diary of the Campaign on 1877, in Armenia and Koordistan, which is a large accurate record of the war, even though it is pro-Turkish. From Armenia, he follows Muhtar Pasha to European Turkey and describes his defence of the lines of Constantinople against the Imperial Russian Army. He is with General Mikhail Skobelev at the headquarters of the Imperial Russian Army when the Treaty of San Stefano is signed in March 1878. He reports this at the Berlin Congress.

At the end of 1878, Williams is in Afghanistan reporting the war, and in 1879 publishes the Notes on the Operations in Lower Afghanistan, 1878–9, with Special Reference to Transport.

In the autumn of 1884, representing the Central News Agency of London, Williams also joins the Gordon Relief Expedition, a British mission to relieve in Major-General Charles George Gordon in Khartoum, Sudan. His is the first dispatch to tell of the loss of Gordon. While in Sudan, he quarrels with Henry H. S. Pearse of The Daily News, who later unsuccessfully sues him. After leaving The Standard in 1884, he works with the Morning Advertiser, but later works with the Daily Chronicle as a war correspondent. He is the only British correspondent to be with the Bulgarian Army under Prince Alexander Joseph of Battenberg during the Serbo-Bulgarian War in November 1885. In the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, he is attached to the Greek forces in Thessaly. His last war reporting is on Herbert Kitchener‘s Sudanese campaign of 1898. His health does not permit his advance to South Africa, but he is still able to compile a diary of the South African War for The Morning Leader.

In 1887, Williams meets with then General of the United States Army, Philip Sheridan, in Washington, D.C. to update the general on European affairs and the prospects of upcoming conflicts.

Williams once tries to bid as a Conservative Party candidate for the House of Commons representative of Leeds West, a borough in Leeds, West Yorkshire, during the 1885 United Kingdom general election. He fails to win the seat against Liberal Party candidate Herbert Gladstone. He once serves as the Chairman of the London district of the Chartered Institute of Journalists from 1893 to 1894. He founds the London Press Club where he also serves as its President from 1896 to 1897.

Williams is wounded three times in action. He is shot in the leg in Egypt in 1885 during General Buller’s retreat from Gubat to Korti.

Williams is a member of the 1st Surrey Rifles, a volunteer unit of the British Army, a member of the London Irish Volunteers, and is a known marksman.

Williams is said to possess a voice of thunder and expresses with terrific energy. He conducts a lecture tour of the United States where he describes the six campaigns, illustrated by limelight photographs. His audience in Brooklyn, New York, is described by The New York Times as highly delighted by his lecture about the hardships and adventures. His presentation is “a feast for the eyes and ears and was highly appreciated by the large audience assembled.” He later tours England, Scotland, and Ireland speaking about his then seven campaigns.

A friend of explorer Henry Morton Stanley, Williams gives him a compass that has been on a number of his expeditions. Stanley takes it with him to Africa and it is now on display at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium.

Williams also writes fiction, including his book John Thaddeus Mackay, a tale about religious tolerance and understanding. With the sanction of Commander in Chief, Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, he edits a book Songs for Soldiers for the March The Camp and the Barracks to improve morale and relieve boredom. Included in the book are a number of songs that he composed. He also writes about ecclesiastical questions, and contributes articles and stories to different periodicals.

Williams is a strong adherent to Wolseley’s military views and policy, and has considerable military knowledge. He also publishes military subjects in several publications such as the United Service Magazine, the National Review, and other periodicals. In 1892, he publishes Life of Sir H. Evelyn Wood, which is controversial as he defends the actions of Wood after the Battle of Majuba Hill in 1881. In 1902, he publishes a pamphlet, entitled Hush Up, in which he protests against the proposed limited official inquiry into the South African War and calls for an investigation.

Early in his career, Williams shares an office with friend and colleague Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, who later becomes Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. They have a standing tradition of always sending out for two beers with payment alternating between each man. Many years later, Williams is in the lobby of the House of Lords and Gascoyne-Cecil approaches him with an outstretched hand and asks, “By the way, Mr. Williams, whose turn is it to stand the beer?”

In 1884, the steamer carrying Williams and colleague Frederic Villiers of The Graphic overturns in the Nile River. Their rescue leads Williams to later commission a unique ivory and gold mitre for the Bishop of London as a thank-offering to God for his safe return from Khartoum.

In Rudyard Kipling‘s play, The Light That Failed, the character of Mr. Nilghai, the war correspondent, is based on Williams.

Williams receives a personal invitation from King Edward VII to attend the funeral of his mother, Queen Victoria.

Both of Williams‘a sons became journalists. Frederick is a noted parliamentary reporter, writer, and historian in Canada. Francis Austin Ward Williams practices journalism in Sydney, Australia.

In the Nile Campaign of 1884-85, application is made to the War Office with the support of the Commander in Chief Lord Wolseley for medals for Willams and correspondent Bennet Burleigh. Williams has been twice requested to take command of some of the men by senior officers on the spot. The Secretary of War is unable to grant the recognition under the rules of the day but writes a letter saying that he regrets that this must be his decision.

Williams is a recipient of the Queen’s Sudan Medal, an award given to British and Egyptian forces which took part in the Sudan campaign between 1896 and 1898.

Field Marshall Garnet Wolseley recognizes the contributions of Williams on the battlefield. He says in a speech that from “Charles Williams, he had at various times received the greatest possible help in the field.”

Williams dies in Brixton, London, on February 9, 1904. He is buried in Nunhead Cemetery in London. His son, journalist Fred Williams, first learns of his father’s death on the wire service he is monitoring at his newspaper in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Williams’s funeral is well attended by the press as well as members of the military including Field Marshal Sir Evelyn Wood. Colleague Henry Nevison writes a long reflection on Williams. It includes, “On the field he possessed a kind of instinctive sense of what was going to happen. When I went to big field-days with him he was already an elderly man, and much broken down with the hardships of a war correspondent’s life; but he invariably appeared at the critical place exactly at the right moment, and I once heard the Duke of Connaught, who was commanding, say, ‘When I see Charlie Williams shut up his telescope, I know it’s all over.’ And now he is gone, with his rage, his generosity, his innocent pride, his faithful championship of every friend, and his memories of so many a strange event. His greatest joy was to encourage youth to follow in his steps, and the world is sadder and duller for his going.”