Charles Cunningham Boycott, land agent and the man who gave the English language the word “boycott,” is born on March 12, 1832, at Burgh St. Peter, Norfolk, England.

Boycott is the eldest surviving son of William Boycatt (1798–1877), rector of Wheatacrebury, Norfolk, and Elizabeth Georgiana Boycatt (née Beevor). The family name is changed to Boycott by his father in 1862. Educated at a boarding school in Blackheath, London, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, he is commissioned ensign in the 39th (Dorsetshire) Regiment of Foot on February 15, 1850, and serves briefly in Ireland. He sells his commission on December 17, 1852, having attained the rank of captain, marries Annie Dunne of Queen’s County (County Laois) in 1852, and leases a farm in south County Tipperary.

In 1855, Boycott leaves for Achill Island, County Mayo, where he sub-leases 2,000 acres and acts as land agent for a friend, Murray McGregor Blacker, a local magistrate. He settles initially near Keem Strand but after some years builds a fine house near Dooagh overlooking Clew Bay. He clashes with local landowners and agents and is regularly involved in litigation. Twice summonsed unsuccessfully for assault (1856, 1859), he is involved (1859–60) in a bitter dispute with a land agent over salvage rights for shipwrecks, one of the few lucrative activities on the island. Achill’s remoteness and the difficulties of wresting a living from its harsh environment adds a roughness to the island’s social relations and probably aggravates Boycott’s tendency to high-handedness.

In 1873, Boycott inherits money and moves to mainland County Mayo, leasing Lough Mask House near Ballinrobe and its surrounding 300 acres. He also becomes agent for John Crichton, 3rd Earl Erne‘s neighbouring estate of 1,500 acres, home to thirty-eight tenant farmers paying rents of £500 a year, of which he receives 10 per cent as agent. He also serves as a magistrate and is unpopular because of his brusque and authoritarian manner, and for denying locals such traditional indulgences as collecting wood from the Lough Mask estate or taking short cuts across his farm. In April 1879, he purchases the 95-acre Kildarra estate between Claremorris and Ballinlough and an adjoining wood for £1,125, taking out a mortgage of £600 which stretches his finances.

Boycott is no brutal tyrant, but he is aloof, stubborn, and pugnacious, and believes that the Irish peasantry is prone to idleness and require firm handling. Such qualities and beliefs are unremarkable enough, but in the peculiar circumstances of the land war in County Mayo, they are enough to catapult this rather ordinary man to worldwide notoriety.

In autumn 1879, concerted land agitation begins in County Mayo, and on August 1, 1879, Boycott receives a notice threatening his life unless he reduces rents. He ignores it and evicts three tenants, which embitter relations on the estate. Lough Mask House is placed under Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) surveillance beginning in November 1879. In August 1880, his farm labourers, encouraged by the Irish National Land League, strike successfully for a wage increase from 7s. –11s. to 9s. –15s. Since the harvest is poor, Lord Erne allows a 10 per cent rent abatement. But in September 1880, when Boycott demands the rent, most tenants seek a 25 per cent abatement. Lord Erne refuses, and on September 22, Boycott attempts to serve processes against eleven defaulters. Servers and police are attacked by an angry crowd of local women and forced to take refuge in Boycott’s house. Almost immediately he is subjected to the ostracism against land grabbers advocated by Charles Stewart Parnell in his September 19 speech at Ennis, County Clare. This weapon proves as devastating against an English land agent as an Irish land-grabber. His servants leave him, labourers refuse to work his land, his walls and fences are destroyed, and local traders refuse to do business with him. He is jeered on the roads, is hissed and hustled by hostile crowds in Ballinrobe, and requires police protection.

The campaign against Boycott is largely orchestrated by Fr. John O’Malley, a local parish priest and president of the Neale branch of the Irish National Land League. It is probably O’Malley who coins the term “boycott” as an alternative to the word “ostracise,” which he believes would mean little to the local peasantry. Propagated by O’Malley’s friend, the American journalist, James Redpath, it is adopted by advocates and opponents alike.

On October 22, 1880, before his story breaks on the world, Boycott gives evidence of his treatment to the Bessborough Commission in Galway. He publicises his plight in an October 18, 1880, letter to The Times, and in a long interview with The Daily News on October 24, which is reprinted in Irish unionist newspapers and arouses considerable sympathy for him. Although he rarely uses his former military rank, he becomes universally known as “Captain Boycott,” since it suits both sides to portray him as someone of social standing. Letters of support appear in unionist papers and the Belfast News Letter sets up a “Boycott Relief Fund” and proposes a relief expedition, portraying Boycott as a peaceable English gentleman unjustly subjected to intimidation.

The prospect of hundreds of armed loyalists descending on County Mayo alarms the government, who announce on November 8 that they will provide protection for a small group of labourers to harvest Boycott’s crops. On November 12, fifty-seven loyalists from counties Cavan and Monaghan, “the Boycott Relief Expedition,” arrive at Lough Mask with an escort of almost a thousand troops. After harvesting Boycott’s crops, they leave on November 26. The entire operation costs £10,000 – about thirty times the value of the crops. Although the expedition passes off largely without incident, it focuses international media attention on the affair and establishes the word “boycott” in English and several other languages as a standard term for communal ostracism.

On November 27, Boycott and his wife go to the Hammam Hotel, Dublin, where he receives death threats. On December 1, he travels to London and then to the United States (March–May 1881) to see Murray McGregor Blacker, the friend from his time on Achill Island who has since settled in Virginia. In an interview with the New York Herald, he criticises the liberal government’s weakness toward the Land League and claims that the Irish land question is an intractable problem that can only be solved in the long term by emigration and industrialisation.

Boycott returns to Lough Mask on September 19, 1881, and at an auction in Westport is mobbed and burned in effigy. This, however, is the last outburst of hostility against him, and as the land agitation wanes so does his unpopularity. Although unsuccessful in efforts to win compensation from the government, he receives a public subscription of £2,000. He remains in County Mayo as Lord Erne’s agent until February 1886, when he obtains the post of land agent for Sir Hugh Adair in Flixton, Suffolk, but he keeps the small Kildarra estate, where he continues to holiday. On December 12, 1888, he gives evidence of his treatment to the parliamentary commission on “Parnellism and crime.”

After suffering from ill-health for some years, Boycott dies at Flixton on June 19, 1897, and is buried in the churchyard of Burgh St. Peter. A British-made film, Captain Boycott (1947), stars Cecil Parker in the title role.

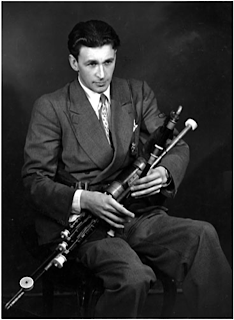

(From: “Boycott, Charles Cunningham” by James Quinn, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Photo credit: Granger NYC/© Granger NYC/Rue des Archives)