The Birmingham pub bombings are carried out on November 21, 1974, when bombs explode in two public houses in Birmingham, England, killing 21 people and injuring 182 others. The bombings are one of the deadliest acts of the Troubles, and the deadliest act of terrorism to occur in England between World War II and the 2005 London bombings.

In 1973, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) extends its campaign to mainland Britain, attacking military and symbolically important targets to both increase pressure on the British government, via popular British opinion, to withdraw from Northern Ireland and to maintain morale amongst their supporters. By 1974, mainland Britain sees an average of one attack — successful or otherwise — every three days.

In the early evening hours of November 21, at least three bombs connected to timing devices are planted inside two separate public houses and outside a bank located in and around central Birmingham. It is unknown precisely when these bombs were planted. If official IRA protocol of preceding attacks upon non-military installations with a 30-minute advance warning to security services is followed, and subsequent eyewitness accounts are accurate, the bombs would have been planted at these locations after 7:30 p.m. and before 7:47 p.m.

According to testimony delivered at the 1975 trial of the six men wrongly convicted of the bombings, the bomb planted inside the Mulberry Bush pub is concealed inside either a duffel bag or briefcase, whereas the bomb planted inside the Tavern in the Town is concealed inside a briefcase or duffel bag (possibly concealed within a large, sealed plastic bag) and Christmas cracker boxes. The remnants of two alarm clocks recovered from the site of each explosion leaves the possibility that two bombs had been planted at each public house. The explosion crater at each location indicates that if two bombs had been planted at each public house, they would each have been placed in the same location and likely the same container.

Reportedly, those who plant the bombs then walk to a preselected phone box to telephone the advance warning to security services. However, the phone box has been vandalised, forcing the caller to find an alternative phone box and thus shortening the amount of time police have to clear the locations.

At 8:11 p.m., an unknown man with a distinct Irish accent telephones the Birmingham Post newspaper. The call is answered by operator Ian Cropper. The caller says, “There is a bomb planted in the Rotunda and there is a bomb in New Street at the tax office. This is Double X,” before terminating the call. (“Double X” is an IRA code word given to authenticate any warning call.) A similar warning is also sent to the Birmingham Evening Mail newspaper, with the anonymous caller again giving the code word, but again failing to name the public houses in which the bombs had been planted.

The Rotunda is a 25-story office block, built in the 1960s, that houses the Mulberry Bush pub on its lower two floors. Within minutes of the warning, police arrive and begin checking the upper floors of the Rotunda, but they do not have sufficient time to clear the crowded pub at street level. At 8:17 p.m., six minutes after the first telephone warning had been delivered to the Birmingham Post, the bomb, which had been concealed inside either a duffel bag or briefcase located ner the rear entrance to the premises, explodes, devastating the pub. The explosion blows a 40-inch crater in the concrete floor, collapsing part of the roof and trapping many casualties beneath girders and concrete blocks. Many buildings near the Rotunda are also damaged, and pedestrians in the street are struck by flying glass from shattered windows. Several of the victims die at the scene, including two youths who had been walking past the premises at the moment of the explosion.

Ten people are killed in this explosion and dozens are injured, including many who lose limbs. Several casualties are impaled by sections of wooden furniture while others have their clothes burned from their bodies. A paramedic called to the scene of this explosion later describes the carnage as being reminiscent of a slaughterhouse. One fireman says that, upon seeing a writhing, “screaming torso,” he begs police to allow a television crew inside the premises to film the dead and dying at the scene, in the hope the IRA would see the consequences of their actions. However, the police refuse this request, fearing the reprisals would be extreme.

The Tavern in the Town is a basement pub on New Street located a short distance from the Rotunda and directly beneath the New Street Tax Office. Patrons there hear the explosion at the Mulberry Bush, but do not believe that the sound, described by one survivor as a “muffled thump,” is an explosion.

Police have begun attempting to clear the Tavern in the Town when, at 8:27 p.m., a second bomb explodes there. The blast is so powerful that several victims are blown through a brick wall. Their remains are wedged between the rubble and live underground electric cables that supply the city centre. One of the first police officers on the scene, Brian Yates, later testifies that the scene which greeted his eyes was “absolutely dreadful,” with several of the dead stacked upon one another, others strewn about the ruined pub, and several screaming survivors staggering aimlessly amongst the debris, rubble, and severed limbs. A survivor says the sound of the explosion is replaced by a “deafening silence” and the smell of burned flesh.

Rescue efforts at the Tavern in the Town are initially hampered as the bomb had been placed at the base of a set of stairs descending from the street, the sole entrance to the premises, had been destroyed in the explosion. The victims whose bodies are blown through a brick wall and wedged between the rubble and underground electric cables take up to three hours to recover, as recovery operations are delayed until the power can be isolated. A passing West Midlands bus is also destroyed in the blast.

This bomb kills nine people outright, and injures everyone in the pub, many severely. Two later die of their injuries. After the second explosion, police evacuate all pubs and businesses in Birmingham city centre and commandeer all available rooms in the nearby City Centre Hotel as an impromptu first-aid post. All bus services into the city centre are halted, and taxi drivers are encouraged to transport those lightly injured in the explosions to hospital. Prior to the arrival of ambulances, rescue workers remove critically injured casualties from each scene upon makeshift stretchers constructed from devices such as tabletops and wooden planks. These severely injured casualties are placed on the pavement and given first aid prior to the arrival of ambulance services.

At 9:15 p.m., a third bomb, concealed inside two plastic bags, is found in the doorway of a Barclays Bank on Hagley Road, approximately two miles from the site of the first two explosions. This device consists of 13.5 pounds of Frangex connected to a timer and is set to detonate at 11:00 p.m. The detonator to the device activates when a policeman prods the bags with his truncheon, but the bomb does not explode. The device is destroyed in a controlled explosion early the following morning.

The bombings stoke considerable anti-Irish sentiment in Birmingham, which then has an Irish community of 100,000. Irish people are ostracised from public places and subjected to physical assaults, verbal abuse and death threats. Both in Birmingham and across England, Irish homes, pubs, businesses and community centres are attacked, in some cases with firebombs. Staff at thirty factories across the Midlands go on strike in protest of the bombings, while workers at airports across England refuse to handle flights bound for Ireland. Bridget Reilly, the mother of the two Irish brothers killed in the Tavern in the Town explosion, is herself refused service in local shops.

The bombings are immediately blamed on the IRA, despite the organisation not having claimed responsibility. Due to anger against Irish people in Birmingham after the bombings, the IRA Army Council places the city “strictly off-limits” to IRA active service units. In Northern Ireland, loyalist paramilitaries launch a wave of revenge attacks on Irish Catholics and within two days of the bombings, five Catholic civilians have been shot dead by loyalists. The Provisional IRA never officially admits responsibility for the Birmingham pub bombings.

Six Irishmen are arrested within hours of the blasts and in 1975 are sentenced to life imprisonment for the bombings. The men, who become known as the Birmingham Six, maintain their innocence and insist police had coerced them into signing false confessions through severe physical and psychological abuse. After 16 years in prison, and a lengthy campaign, their convictions are declared unsafe and unsatisfactory, and quashed by the Court of Appeal in 1991. The episode is seen as one of the worst miscarriages of justice in British legal history.

In 2001, each of the Birmingham Six is subsequently paid between £840,000 and £1.2 million in compensation.

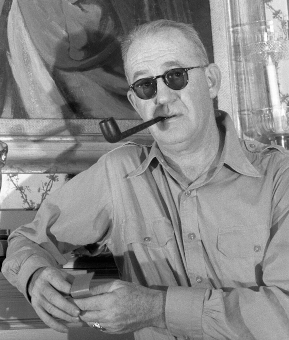

(Pictured: The Mulberry Bush pub after the November 21, 1974, bombing)