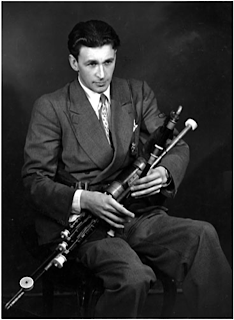

Séamus Ennis (Irish: Séamas Mac Aonghusa), Irish musician, singer and Irish music collector, dies in Naul, County Dublin, on October 5, 1982. He is most noted for his uilleann pipe playing and is partly responsible for the revival of the instrument during the twentieth century, having co-founded Na Píobairí Uilleann, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to the promotion of the uilleann pipes and its music. He is recognised for preserving almost 2,000 Irish songs and dance-tunes as part of the work he does with the Irish Folklore Commission. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest uilleann pipers of all time.

Ennis’s father, James, works for the Irish civil service at Naul, County Dublin. In 1908, James Ennis is in a pawn shop in London and purchases a bag containing the pieces of a set of old uilleann pipes. They were made in the mid nineteenth century by Coyne Pipemakers of Thomas Street in Dublin. In 1912, he comes in first in the Oireachtas competition for warpipes and second in the uilleann pipes. He is also a prize-winning dancer. In 1916, he marries Mary Josephine McCabe, an accomplished fiddle player from County Monaghan. They have six children, Angela, Séamus, Barbara, and twins, Cormac and Ursula (Pixie) and Desmond. Séamus is born on May 5, 1919, in Jamestown in Finglas, Dublin. James Ennis is a member of the Fingal trio, which includes Frank O’Higgins on fiddle and John Cawley on flute, and performs regularly with them on the radio. At the age of thirteen, Séamus starts receiving lessons on the pipes from his father. He attends a Gaelscoil, Cholmcille, and a Gaelcholáiste, Coláiste Mhuire, which gives him a knowledge of the Irish language that serves him well in later life. He sits in an exam to become Employment Exchange clerk but is too far down the list to be offered a job. He is twenty and unemployed.

Colm Ó Lochlainn is editor of Irish Street Ballads and a friend of the Ennis family. In 1938, Ennis confides in Colm that he intends to move to England to join the British Army. Colm immediately offers him a job at The Three Candles Press. There Ennis learns all aspects of the printing trade. This includes writing down slow airs for printed scores – a skill which later proves important. Colm is director of an Irish language choir, An Claisceadal, which Ennis joins. In 1942, during The Emergency, shortages and rationing mean that things become difficult in the printing trade. Professor Seamus Ó Duilearge of the Irish Folklore Commission hires the 23-year-old to collect songs. He is given “pen, paper and pushbike” and a salary of three pounds per week. Off he goes to Connemara.

From 1942 to 1947, working for the Irish Folklore Commission, Ennis collects songs in west Munster; counties Galway, Cavan, Mayo, Donegal, Kerry; the Aran Islands and the Scottish Hebrides. His knowledge of Scottish Gaelic enables him to transcribe much of the John Lorne Campbell collection of songs. Elizabeth Cronin of Ballyvourney, County Cork, is so keen to chat to Ennis on his visits that she writes down her own songs and hands them over as he arrives, and then gets down to conversation. He has a natural empathy with the musicians and singers he meets. In August 1947, he starts work as an outside broadcast officer with Raidió Éireann. He is a presenter and records Willie Clancy, Seán Reid and Micho Russell for the first time. There is an air of authority in his voice. In 1951, Alan Lomax and Jean Ritchie arrived from the United States to record Irish songs and tunes. The tables are turned as Ennis becomes the subject of someone else’s collection. There is a photograph from 1952/53 showing Ritchie huddled over the tape recorder while Ennis plays uilleann pipes.

Late in 1951, Ennis joins the BBC. He moves to London to work with producer Brian George. In 1952, he marries Margaret Glynn. They have two children, the organist Catherine Ennis and Christopher. His job is to record the traditional music of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland and to present it on the BBC Home Service. The programme is called As I Roved Out and runs until 1958. Meeting up with Alan Lomax again, he is largely responsible for the album Folk and Primitive Music (volume on Ireland) on the Columbia Records label.

In 1958, after his contract with the BBC is not renewed, Ennis starts doing freelance work, first in England then back in Ireland, with the new TV station Teilifis Éireann. Soon he is relying totally on his musical ability to make a living. About this time, his marriage breaks down and he returns to Ireland. He suffers from tuberculosis and is ill for some time. In 1964, he performs at the Newport Folk Festival. His father gives him the pipes he had bought in 1908. Although most pipers can be classed as playing in a tight style or an open style, Ennis is in between. He is a master of the slow air, knowing how to decorate long notes with taste and discreet variation.

Two events will live in legend among pipers. The first is in Bettystown, County Meath, in 1968, when the society of Irish pipers, Na Píobairí Uilleann, is formed. Breandán Breathnach is playing a tape of his own piping. Ennis asks, “What year?” Breandán replies, “1948.” Ennis says, “So I thought.” For a couple of hours the younger players perform while Ennis sits in silence. Eventually he is asked to play. Slowly he takes off his coat and rolls up his sleeves. He spends 20 minutes tuning up his 130-year-old pipes. He then asks the gathering whether all the tape recorders are ready and proceeds to play for over an hour. To everyone’s astonishment he then offers his precious pipes to Willie Clancy to play a set. Clancy demurs but eventually gives in. Next, Liam O’Flynn is asked to play them, and so on, round the room. The second unforgettable session is in Dowlings’ Pub in Prosperous, County Kildare. Christy Moore is there, as well as most of the future members of Planxty.

Ennis never runs any school of piping but his enthusiasm infuses everyone he meets. In the early 1970s, he shares a house with Liam O’Flynn for almost three years. Finally, he purchases a piece of land in Naul and lives in a mobile home there. One of his last performances is at the Willie Clancy Summer School in 1982. He dies on October 5, 1982. His pipes are bequeathed to Liam O’Flynn. Radio producer Peter Browne produces a compilation of his performances, called The Return from Fingal, spanning 40 years.

Séamus Ennis Road in his native Finglas is named in his honour. The Séamus Ennis Arts Centre in Naul is opened in his honour, to commemorate his work and to promote the traditional arts. He is also the subject of Christy Moore’s song “The Easter Snow.” This is the title of a slow air Ennis used to play, and one after which he named his final home in Naul.