William Conor, figure and portrait painter, dies on February 6, 1968, at his home in Salisbury Avenue, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

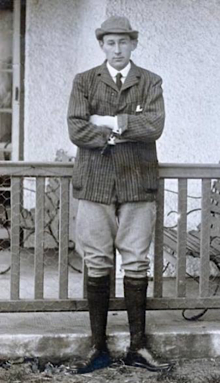

Conor is born on May 9, 1881, in Fortingale Street, Belfast, the third son and fourth child of William Connor, a tinsmith and sheet metal worker, who later becomes a gas fitter, and Mary Connor (née Wallace). He is educated at the Clifton Park central national school, where his artistic abilities are noticed by his music teacher. In 1894, he enrolls at the Belfast government school of design. He is a very successful student, and by 1903 has become an assistant teacher. He completes his studies in 1904, and begins an apprenticeship with the Belfast firm of lithographers, David Allen and Son. Through his work in the poster design department he develops an enthusiasm for using crayons on a textured surface. This becomes a characteristic feature of his later drawings. In these early years he first starts recording images of Belfast life, often sketched from behind a folded newspaper in the street. Influenced by the Gaelic revival, in the years 1907–9 he signs his name in several different ways such as “Liam” and “Liam Conor.” In later years he signs himself simply “Conor.”

Having abandoned his career as a lithographer around 1910, Conor concentrates his efforts on painting professionally. He begins exhibiting with the Belfast Art Society in 1910, and in the period that follows he spends time in Craigavad, County Down, the Blasket Islands in County Kerry, Dublin, and Donegal. During a visit to Paris, which he later recalls as being in 1912 and 1913, he meets the painter André Lhote. After his return to Belfast he is elected to the committee of the Belfast Art Society in 1913. On the outbreak of World War I, he is commissioned by the British government to record the everyday activities of munitions workers and soldiers in Ulster. His pictures mostly show soldiers in training and various scenes from the home front, including the work of women in munitions factories and hospitals. Described as “vigorous and personable, if rather folksy . . . effectively uniformed versions of the tinkers and shipyard workers for which he subsequently became known,” these paintings are exhibited and subsequently, in 1916, auctioned for the Ulster Volunteer Patriotic Fund. His long association with the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) begins in 1918 and he shows up to 200 works at the academy over the next forty-nine years.

In 1921, Conor moves to London, where he becomes acquainted with, among others, Sir William Orpen, Sir John Lavery, and Augustus John. He becomes a member of the Chelsea Arts Club, and contributes four paintings to the National Portrait Society as part of its spring exhibition in 1921. His friendship with Lavery is significant. Through him Conor receives a commission to paint the opening of the first Northern Ireland parliament in June 1921. He goes on to exhibit with a variety of influential bodies, including the Royal Academy of Arts, the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. In 1922, The Twelfth, executed c.1918, is shown in the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris, under the title Le cortège Orangiste à Belfast, as part of the World Congress of the Irish Race. He is represented at the Paris salon in 1923 and the following year he has a successful exhibition at the St. Stephen’s Green Gallery, Dublin.

In 1926, Conor travels to Philadelphia and New York, where, during his nine-month stay, he receives numerous commissions for portraits and has work shown in the Babcock Galleries, the Brooklyn Art Gallery, and the American Irish Historical Society. In 1932, he designs the costumes for the principals in the Pageant of St. Patrick, which marks the 1,500th anniversary of the saint’s coming to Ireland. That year also sees the unveiling of his mural Ulster Past and Present at the Belfast Municipal Museum and Art Gallery. Measuring 2.8 by 7.4 metres, it is at the time the largest mural in the country. During World War II he is again appointed an official war artist and his work is represented at the exhibition of war artists at the National Gallery, London, in 1941. His book The Irish Scene is published in 1944, and though it sells well, the subsequent bankruptcy of his publishers mean that Conor receives no royalties. He also provides the illustrations for books by Lynn C. Doyle, the pseudonym of his friend Leslie Montgomery.

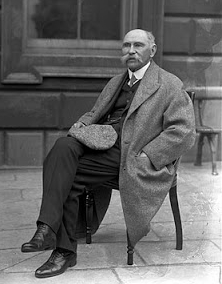

Although Conor is best known for his depictions of the everyday life of people in his native Belfast, in which he attempts to capture the “flash of humour which lightens their daily toil,” he also produces landscapes and portraits. His sitters included Douglas Hyde, St. John Greer Ervine, Charles D’Arcy, and Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 7th Marquess of Londonderry. The Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts organises several successful Conor exhibitions. Their one-man show of 1945 becomes the first to tour the province, while their exhibition of his work in 1954 has an attendance in excess of 2,800. Conor closes his long-established studio on Stranmillis Road in 1960 but continuea to exhibit, notably with the Bell Gallery in 1964, 1966, and 1967.

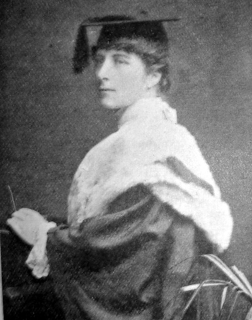

The first Irishman to become a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Conor is a founder member of the Ulster Academy (later the Royal Ulster Academy), and from 1957 to 1964 serves as its president. In 1938 he becomes an associate member of the RHA, and in 1947 he receives full membership. He is awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1952, an honorary MA from Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) in 1957, and a civil-list pension in 1959.

Conor dies on February 6, 1968, at his home in Salisbury Avenue, Belfast, and is buried in Carnmoney churchyard. He never marries. His work is represented in galleries and institutions throughout Ireland and Great Britain, including the Ulster Museum, Ulster Folk and Transport Museums, Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane, the Imperial War Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

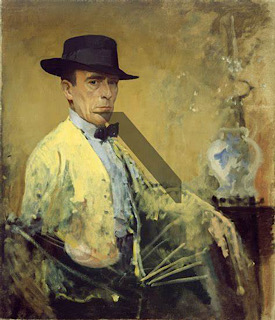

(From: “Conor, William” by Frances Clarke, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009 | Pictured: “William Conor,” oil on canvas by Gladys Maccabe, Ulster Folk Museum)