George Noble Plunkett, scholar and revolutionary, is born on December 3, 1851, at 1 Aungier Street, Dublin, the youngest and only survivor from infancy of the three children of Patrick Joseph Plunkett (1817–1918), builder and politician, and his wife, Elizabeth (née Noble). The Plunketts are Catholic, claiming collateral descent from Archbishop of Armagh Oliver Plunkett, and nationalist: the two drummers from the republican army at Vinegar Hill in 1798 visit George’s cradle.

Plunkett is educated expensively: at a primary school in Nice, making him fluent in French and Italian, then at Clongowes Wood College, and, from 1872, at Trinity College Dublin (TCD), where his generous allowance allows him to study renaissance and medieval art. He enrolls at King’s Inns in 1870 and the Middle Temple in 1874, but is not called to the bar until 1886. While there he befriends Oscar Wilde and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. In 1877, he endows a university gold medal for Irish speakers and publishes a book of poems, God’s Chosen Festival, and the following year he issues a pamphlet, The Early Life of Henry Grattan. He also writes articles for magazines, editing a short-lived one, Hibernia, for eighteen months from 1882. In 1883, he donates funds and property to the nursing order of the Little Company of Mary (Blue Sisters), and on April 4, 1884, Pope Leo XIII makes him a count.

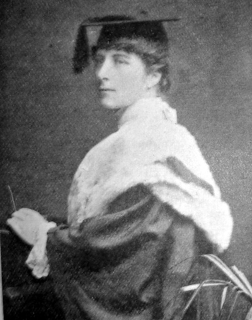

On June 26, 1884, Plunkett marries Mary Josephine Cranny (1858–1944). The couple has seven children: Philomena (Mimi) (b. 1886), Joseph (b. 1887), Mary Josephine (Moya) (b. 1889), Geraldine (b. 1891), George Oliver (b. 1894), Fiona (b. 1896), and Eoin (Jack) (b. 1897).

Plunkett surprises many in 1890 by declaring for Charles Stewart Parnell against the Catholic hierarchy. In the 1892 United Kingdom general election in Ireland he is a Parnellite candidate for Mid Tyrone but withdraws from a potential three-cornered fight lest he let in the unionist. He is sole nationalist candidate for Dublin St. Stephen’s Green in the 1895 United Kingdom general election in Ireland, and at an 1898 by-election there he cuts the unionist majority to 138 votes. The reunited Irish Party wins the seat in 1900.

In 1894, Plunkett part-edits Charles O’Kelly‘s memoir The Jacobite War in Ireland. By 1900, when he publishes the standard biography Sandro Botticelli, he is supplementing his income by renewed artistic studies, which until 1923 finances his lease of Kilternan Abbey, County Dublin. His Pinelli (1908) is followed by Architecture of Dublin, and, in 1911, by his revised edition of Margaret McNair Stokes‘s Early Christian Art in Ireland. In 1907, he becomes director of the National Museum of Ireland, where he increases annual visits from 100 to 3,000.

Joseph Plunkett swears his father into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in April 1916, sending him secretly to seek German aid and a papal blessing for the projected Easter rising. After its defeat, Plunkett is sacked by the National Museum of Ireland and deported with the countess to Oxford, and the following January he is expelled by the Royal Dublin Society (RDS). This earns him nomination as the surviving rebels’ candidate in the North Roscommon by-election. He returns to Ireland illegally on January 31, 1917, and wins the seat easily three days later. Pledging abstention from attendance at Westminster in accordance with Sinn Féin policy, he initiates a Republican Liberty League, which coalesces with similar groups such as Sinn Féin. In October this front becomes the new Sinn Féin, committed to Plunkett’s republic rather than to the “king, lords and commons“ of Arthur Griffith. Plunkett and Griffith become the new party’s vice-presidents, under Éamon de Valera.

On May 18, 1918, Plunkett is interned again. Released after Sinn Féin’s general election landslide (in which he is returned unopposed), he presides, Sinn Féin’s oldest MP, at the planning meeting for Dáil Éireann on January 17, 1919, and at its opening session on January 21. On the 22nd he is made foreign affairs minister by Cathal Brugha, an appointment reaffirmed by de Valera on April 10. He criticises his president for advocating a continuing Irish external relationship with Britain, and fails to organise an Irish foreign service. In February 1921, de Valera makes Robert Brennan his departmental secretary and a ministry takes shape, while Plunkett publishes a book of poems, Ariel. After uncontested “southern Irish“ elections to the Second Dáil, de Valera moves his implacable foreign minister from the cabinet to a tailor-made portfolio of fine arts. Plunkett’s Dante sexcentenary commemoration is overshadowed by news of the Anglo–Irish Treaty. Opposing this, Plunkett cites his oath to the republic and its martyrs including his son. He leaves his ministry on January 9, 1922.

Plunkett chairs the anti-treaty Cumann na Poblachta, which loses the June general election, though he is returned again unopposed. In the Irish Civil War the treatyites intern him and the republicans appoint him to their council of state. In the August 1923 Irish general election, his first electoral contest since 1917, the interned count tops the poll in County Roscommon. He is released in December.

When de Valera forms Fianna Fáil in 1926, Plunkett stays with Sinn Féin, and loses his deposit in the June 1927 Irish general election. A year later he publishes his last poetry collection, Eros. He runs for a new Cumann Poblachta na hÉireann in a County Galway by-election in 1936, but loses his deposit again. On December 8, 1938, with the other six surviving abstentionist Second Dáil TDs, he transfers republican sovereignty to the IRA Army Council.

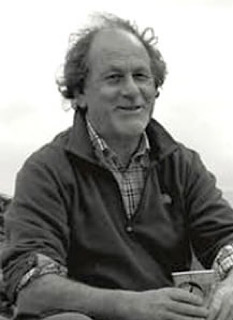

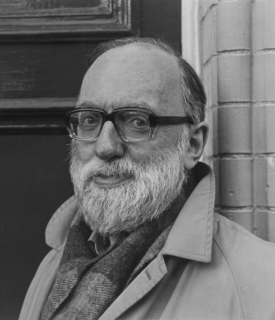

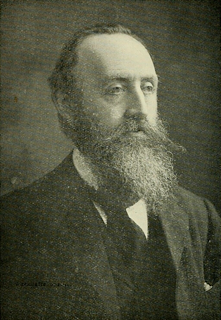

Plunkett is a big man with a black beard which whitens steadily after his fiftieth birthday. He is always formally pleasant and courteous. His oratory is described by M. J. MacManus as “level, cultured tones . . . [more] used to addressing the members of a learned society than to the rough and tumble of the hustings” (The Irish Press, March 15, 1948). Theoretically and practically, he is more scholar than politician. His portrait is on display at the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (RSAI).

Plunkett dies from cancer on March 12, 1948, and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, survived by his children Geraldine (wife of Thomas Dillon), Fiona, and Jack. His grandson Joseph (1928–66), son of George Oliver Plunkett, inherits the title.

(From: “Plunkett, Count George Noble” by D. R. O’Connor Lysaght, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)